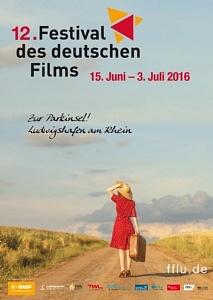

The Berlinale is the German film festival that gets all the media attention. But there’s another game in town, and this summer it celebrated another record: 112,000 tickets were sold at the Festival of German Film in Ludwigshafen, up from 88,000 the previous year. Second only to the Berlinale in the number of German productions on film screens, the film festival in Ludwigshafen has been able to increase its appeal and audience figures steadily and impressively from year to year. Attendance is doubtlessly helped by the uniquely relaxed atmosphere where fans watch films on an island in the middle of the Rhine and then hang out in this park-like setting under trees and along the banks of the river, sitting on benches and in deck chairs with beer in hand and cinema on the mind.

Given the fact that really big-budget productions and internationally recognizable stars rarely appear at Ludwigshafen, this success seems surprising. The festival isn’t in the same league as the Berlinale and its premieres and glamorous red carpet events. It also seems to run contrary to mainstream trends which have seen a general decline in the sale of cinema tickets and a shift away from watching movies in public spaces. So what has allowed the festival to increase its ticket sales more than ten-fold since it began in 2005?

According to festival director Michael Kötz, one important reason for its appeal is the event’s concept as an audience festival. Rather than being industry-oriented, the focus is on the promotion of a dialogue between film artists and spectators, creating a platform where German cinema can connect with its intended and primary audience. While this engagement with the audience has been a primary aim since the festival’s inception, this dialogue appears to have been anticipated originally as a one-way affair, in effect as a mission to educate audiences about cinematic art and native auteur cinema.

A platform where German cinema can connect with its intended and primary audience.

Established in 2005, the Festival of German Film was as a response to changes in the German film industry in general, especially the creation of the German Film Academy modelled on the American institution and a corresponding award ceremony for the German Film prize, the Lola. Just two days after the first glamorous celebration of the newly established academy in 2005, a group of film artists, including the directors Robert Thalheim and Peter Lilienthal and actor Hanna Schygulla, took a stand against what they perceived as the sell-out of film art to an increasingly globalized culture industry. They awarded the winner of the new Ludwigshafen festival the German Prize for Film Art and published a manifesto, the Ludwigshafener Position, which set out the festival’s main aims and principles. “We do not believe in the myth of a German film industry,” they claimed, “German cinema will be art, or it will not be at all.” They rejected commercial considerations as a primary factor in filmmaking and insisted on aesthetic innovation as the path to their intended audience, to “tear open their eyes and see the world in new ways.” Only through aesthetic innovation, artistic integrity and freedom from commercial pressures would it be possible, in their opinion, to become commercially viable in the long term. Learning from the mistakes of their Oberhausen ‘forefathers,’ they acknowledged cinema’s dependence on its paying audience, but believed that only the highest artistic standards could in the end guarantee commercial success.

The response to the new festival and the manifesto was mixed. While the exclusive attention to home-grown cinema was welcomed by many in the industry, the manifesto itself drew negative comments. Some saw it as a ploy by the tourism board to drum up business by commodifying national cinema and using it to create a marketable culture event. Critics described the festival as a regressive step back to elitist and protected national filmmaking that is ignorant of the changing conditions of production, parochial and out of touch with audiences.

More surprisingly, however, the manifesto was also rejected by the very people to whom it offered an exhibition space and discussion forum. Representatives of the Berlin School were especially critical of the manifesto, declaring it ridiculous, without substance, idealistic and not suitable to address the lack of appeal of home-grown auteur cinema to its target audience. While directors such as Christoph Hochhäusler and Benjamin Heisenberg shared the manifesto’s opposition towards dominant modes of film production in Germany, they objected to its assumption that there is an interested audience out there, it just hasn’t been reached. Hochhäusler shifted the blame: “I believe that it is impossible to create a new cinema without a new audience.” This echoed the view of many film artists and critics – a resigned belief that German audiences are unwilling and more importantly unable to handle sophisticated and challenging cinema, a result of a diet of predictable and mediocre television fare.

Taking stock now after more than 10 years, do the impressive audience figures suggest that the festival has succeeded in creating its own new audience? Has it achieved its original mission and been able to open the eyes of (reluctant?) audiences and make them appreciate, learn to like, or even demand auteur cinema? Perhaps, but the relationship between film artists and their audiences is complex, and it seems that the exchange between artists and audience has evolved beyond the original didactic intentions of the festival.

There is no doubt that some art house films get bigger, more diverse audiences through the festival than might be the case with other festivals catering mainly to serious cinephiles. The festival format, with at times spirited exchanges between artists and spectators at post-screening Q & A sessions, contributes to the special atmosphere regularly praised by all participants. But as the evolution of the festival suggests, its audience’s role exceeds that of just consumers. Not only is one of the prizes selected by the audience, but a look at the festival’s programming over the years indicates that dominant audience tastes have found their way into the selection of films and the media coverage of the event.

There is glamour at Ludwigshafen: the red carpet regularly features Germany’s favourite TV stars, often known from the Tatort crime series, and the daily report on festival events focuses on stars, genres, and plot summaries rather than film form or style. Fun, not auteurism, is the watchword at Ludwigshafen. The opening film usually presents light fare in the shape of a comedy and banks on the audience’s recognition of well-known faces, names, and plot lines. In 2015, the festival opened with Dani Levy’s Der Liebling des Himmels, a relationship comedy starring Mario Adorf, Axel Milberg, and TV host Günther Jauch playing himself.

Audience tastes have found their way into the selection of films.

Over the years Ludwigshafen has grown not only in terms of audience numbers, but also in the expansion of its profile. More program lines have been added reflecting the importance of television for Germany’s film production and highlighting the medium’s role in shaping viewing habits and audience tastes. Although most films running in competition are already financed at least in part by TV companies, in 2014 an additional media prize was introduced to honour an outstanding television production. By 2015, both in the Competition as well as in the relatively new category Kriminell Gut, the program included a number of episodes that were made specifically for long-running TV series and were launched at the festival as media events.

Audience influence is also felt in the Wiedersehen program category highlighting spectator favourites from past festivals. There’s a clear preference for plot-driven TV-style narratives that focus on the fictionalization of current social problems or issues. The visual language and narrative conventions of these films are familiar from television productions, leaving out formally more challenging or unusual films. The festival’s original auteur ambitions appear to have taken somewhat of a backseat. If instances of formal experimentation can reach and are welcomed by a wider audience at Ludwigshafen, it often happens in genres dear to the heart of the German TV-schooled audience. So even if it might have been anticipated differently in 2005, the film festival in Ludwigshafen has developed into an event that truly deserves to be called an audience festival.

Watch a promotional video produced by the Festival of German Film (the video is in German, but with long stretches of just visuals):

Images courtesy of the Festival of German Film.