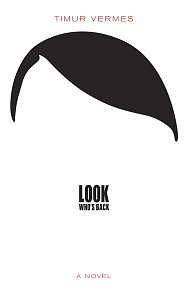

The novel’s arresting cover must have made people stop and look. In a country where people still use bookstores to find out about new books, one look at the all-white cover with only the barest outlines of a head – a swath of hair that falls to the left, and a small, square moustache formed by the title of the book, Er ist wieder da – and every reader will know: this is a book about Hitler.

The novel’s arresting cover must have made people stop and look. In a country where people still use bookstores to find out about new books, one look at the all-white cover with only the barest outlines of a head – a swath of hair that falls to the left, and a small, square moustache formed by the title of the book, Er ist wieder da – and every reader will know: this is a book about Hitler.

Timur Vermes’s Er ist wieder da, which appeared in English in 2015 as Look Who’s Back, was a German publishing sensation in 2012. It was Vermes’s first novel; up until then he had ghost-written a few non-fiction books. The novel remained on the top of the bestseller lists for over two years.

The conceit of this satire was branded “plausible” by the German weekly Die Zeit. Hitler wakes up on a street in Berlin. It’s not 1945, but 2011, and he has a slight headache. He can’t remember anything since the bunker, and is astonished to see that Berlin has not been reduced to rubble. People think he’s a Hitler impersonator, and the amusement people get from his crazy monologues propels him to a career as a tv guest and YouTube phenomenon. His on-the-street interviews make him into a media star, and he becomes a sort of ironic commenter on the state of German affairs in the age of Merkel.

What this novel doesn’t do, however, is explain why there is still the fixation with Hitler in the first place. As a 400-page satire, it can wear your nerves down a little. It reminded me of Dani Levy’s flawed film My Führer – a half-funny joke that goes on far too long. One could say that the novel is just the latest case of the “Hitleritis” plague (to quote Cornelia Fiedler in the Süddeutsche Zeitung) that started with the appearance of the film Downfall in 2004.

But I think there’s more going on here. I am not as concerned as others might be that this reflects a dangerous slip on the part of German society; I really don’t think there are many credible signs that Germany could enslave itself again in fascism. Nor do I think that the novel’s gimmick really helps us understand the social or in particular the media landscape of contemporary Germany – the plot device is too concerned with itself to be much of a spotlight on German society as a whole.

Rather, I look at the appearance of these kinds of satires as a sort of surrender. It is so difficult in the heterogeneous 21st century to imagine that a man like Hitler could have held such sway over a nation. Downfall, My Führer, Look Who’s Back – these are all documents of disbelief. Anyone who knows Germany today certainly recognizes that there are strains of extremism and intolerance there. On their own, those streams, while despicable, are similar to the strains of extremism found in other countries: there’s no indication that they would ever manage to gain control of the country, though one must be ever vigilant to ensure that they don’t.

The cult of Hitler that was Nazism is unfathomable to most people. When I teach a course on culture of the Third Reich, students remark again and again how they can’t understand why the Germans followed him with such devotion. They learn about the social and economic conditions, they hear about the history of anti-Semitism in central Europe, they read about the Versailles Treaty, they learn about leading Nazis’ distrust of modernism, but none of that explain satisfactorily Hitler’s hold on the Nazi party and the nation as a whole ca. 1935.

-

Writing

-

Overall

Summary

To reduce Nazism to Hitler, especially today, is dangerous. It might prevent a more thorough understanding of the complex web of forces that led to the Third Reich. It could lead to that fear that has almost become a cliché: those who don’t understand history are doomed to repeat it. But books like Look Who’s Back show that Hitler remains a looming figure in the German consciousness, and in fact further that place for the dictator. What is needed is something that dispels the fascination. The amount of research on Hitler and the Third Reich is crushingly large, but it still hasn’t been able to demystify the man.